Featured Videos

-

Therapy Balls for pain relief and fascial reorganization.

-

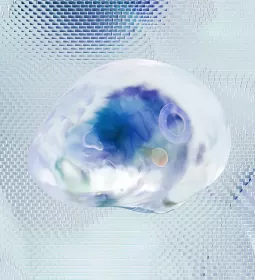

Examining the fibroblast cell and its functions in the body, including making up the fibers for the fabric of the human body.

-

Author Ruth Werner expands on her article about why people faint and interviews a first responder to dive deeper into the topic.

-

AnatomySCAPES debuts its video "The Sciatic Nerve: A 3D View from the Inside Out" in Massage & Bodywork magazine to dive deep into the sciatic nerve and its 3D fascial reality.