Rhythms are a central part of life and provide an important lens through which to understand the search for good health. In humans and other mammals, the “beat” that sustains many rhythms is located in the brain and often generated by groups of nerve cells, which act as natural pacemakers, orchestrating a range of rhythms with significant implications for both health and disease.

Craniosacral therapy (CST) practitioners have long described a subtle rhythm distinct from heartbeat and breath—the craniosacral rhythm (CSR). For decades, this rhythm has guided assessments, therapeutic interventions, and clinical outcomes. Yet, for many years, critics questioned whether the CSR existed as an independent physiological rhythm, or whether therapists simply perceived other motions or imagined what they expected to feel. Early measurement tools were not sensitive enough to capture the subtle micromovements associated with the CSR. As a result, practitioners had little objective evidence beyond palpation to support their observations.

Manual therapists have relied on palpation of the CSR for decades as a central guide in their interventions, consistently reporting profound physiological changes when the rhythm is balanced. What practitioners once perceived only through their hands is now being confirmed and explained by modern research. Advances in sensitive measurement technologies and extensive exploration of bodily rhythms have helped to define the CSR as a distinct physiological rhythm. Science has clarified not only that this rhythm exists but so do aspects of the mechanisms underlying it.

Recent studies using advanced measurement technology have resolved much of the earlier debate. Research now demonstrates that the CSR is a distinct, measurable rhythm operating at 4–8 cycles per minute (cpm), separate from respiration and cardiac activity.1 This recognition bridges a long-standing gap between the experiential wisdom of practitioners and the expectations of the scientific community.

History of Craniosacral Therapy and the CSR

For those unfamiliar with craniosacral therapy, let’s look at its origins.

Dr. William Garner Sutherland

The palpatory observations of rhythmic motions of the head in osteopathic manual therapy can be traced back to Dr. William G. Sutherland, an osteopath in the early 20th century who proposed what he called the primary respiratory mechanism. Sutherland described the subtle expansion and contraction of the head and believed these rhythmic motions underpinned human health and vitality. Notably, he identified recurring phases of movement—flexion and extension—that practitioners could palpate.2

For decades, evidence of palpable head rhythms distinct from respiratory and cardiac rhythms was inconsistent.

Sutherland suggested these motions were driven by an inherent motility of the brain, expressed via the central nervous system. His model emphasized that this rhythm was distinct from lung breathing or the cardiac pulse. Although critics at the time dismissed his claims as untestable, Sutherland’s vision established a conceptual framework that inspired generations of osteopaths and manual therapists.

Dr. John E. Upledger

In the 1970s, Dr. John E. Upledger, an osteopathic physician, observed a slow rhythmic motion of the spinal dura mater (the outer membrane surrounding the spinal cord) during a neck surgery. The observed movement of the dura mater was reported to be independent of breathing and heartbeat. This direct surgical observation inspired him to investigate what he called the “craniosacral rhythm.”

Upledger’s contribution went far beyond observation: He developed a structured methodology for palpating the CSR, identifying restrictions and implementing a system of manual interventions to facilitate changes in whole-body tissues. He introduced the name CranioSacral Therapy3 and created an explanatory model to help conceptualize the palpable CSR.

Equally important, he emphasized a therapeutic philosophy of listening to the body’s inherent wisdom and encouraged practitioners to work with sensitivity and respect for the patient’s inner processes.

Through his teaching, clinical practice, and research initiatives, Upledger formalized CST into a distinct therapeutic discipline, allowing what began as surgical observation to become a transformative therapeutic approach. Upledger remained open to new ideas and developments throughout his life. Rather than presenting CST as a finished science, he recognized that further research could shed new light on its mechanisms and applications.

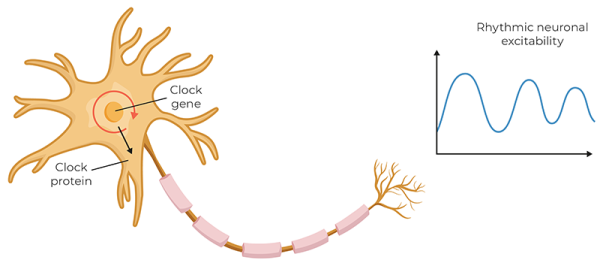

Rhythms and the 2017 Nobel Prize

To understand CSR better, we can look at another one of the body’s most important rhythms. The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael W. Young for their work describing the molecular mechanisms of the circadian rhythm. All aspects of our organs and cellular functions are governed by circadian rhythms, the most obvious being our sleep-wake cycle. The biological clock’s cycle is generated by a feedback loop, in which genes are activated that trigger the production of proteins. As protein levels build to a critical point, the genes are switched off. Over time, the proteins degrade to a level that allows the genes to switch back on, restarting the cycle.

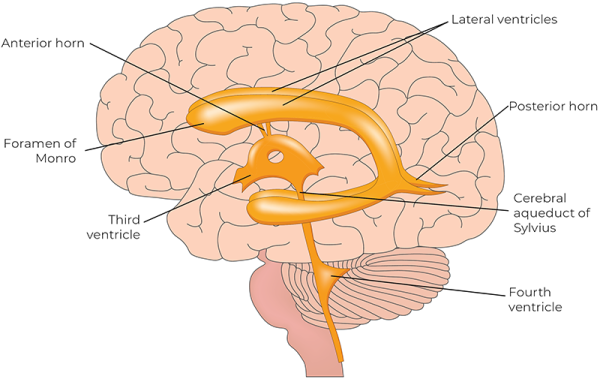

The pacemaker for the circadian rhythm is in the hypothalamus, near the third ventricle of the brain. This pacemaker generates an internal representation of solar time that is conveyed to every cell in the body, coordinating the daily cycles of physiology and behavior. Today, there is growing recognition that chronic disruption of circadian rhythms has profound effects on our health. Is there a link between what we’re learning about the pacemaker of the circadian rhythm and CSR?

Research on the CSR

Foundational studies on circadian rhythms have already led to a paradigm shift in how we understand biological rhythms and health. In relation to the CSR, research areas have historically focused on a rhythm around 6 cycles per minute (cpm). However, the connection to rhythms palpated by manual therapists remained unclear. For decades, evidence of palpable head rhythms distinct from respiratory and cardiac rhythms was inconsistent.

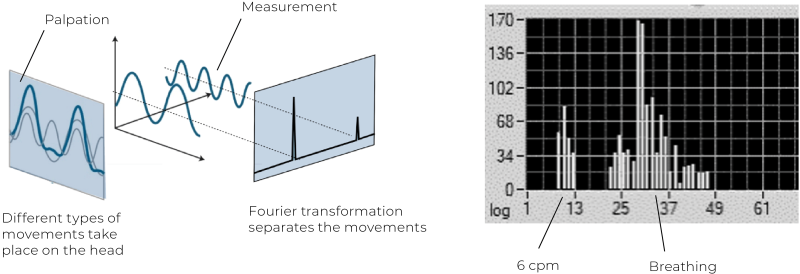

In 2021, Dr. Thomas Rasmussen and Karl Christian Meulengracht published a landmark study, “Direct Measurement of the Rhythmic Motions of the Human Head Identifies a Third Rhythm.”4 Using robotics and software analysis, this was the first direct measurement of cranial rhythms. Micromovements of the head were recorded in 50 healthy adults, alongside respiratory and cardiac rhythms. Their results revealed three consistent rhythms across all participants:

-

Cardiac rhythm—averaging 57 cpm (range 44–78)

-

Respiratory rhythm—averaging 14 cpm (range 9–24)

-

A slower “third rhythm”—averaging 6.16 cpm (range 4.25–7.07)

The third rhythm showed a waveform consistent with palpatory descriptions of the CSR, including flexion, neutral zone, and extension phases. Its amplitude averaged 58 micrometers—large enough to be detected by skilled palpation. This rhythm was distinct from both respiration and cardiac activity, validating long-standing claims by CST practitioners. A key challenge in CSR research has been distinguishing this rhythm from respiratory rhythms. Rasmussen and Meulengracht addressed this by measuring both body and head respiratory rhythms simultaneously.5 Using Fourier transformation analysis, they successfully separated individual rhythms on the head. This clarified why some practitioners palpate rhythms ranging between 4 and 14 cpm—a likely mixing of the CSR and respiratory rhythms. More experienced practitioners, however, consistently identify the slower rhythm near 6 cpm, as documented in a large palpation study of 734 individuals by Nicette Sergueef.6

Today, the normative range of the CSR is converging on 4–8 cpm, supported by both palpatory7 and measurement studies.8 Additional research by Kenneth Nelson and colleagues, using Laser Doppler flowmetry, also identified oscillations in cerebral blood flow near 6 cpm, correlating with palpated rhythms.9

A Neurophysiological Basis for CSR

Early in the development of CST, Upledger proposed the Pressurestat Model as a way of explaining the rhythm practitioners palpated. This model suggested that cycles of cerebrospinal fluid production and reabsorption generated cranial bone motion. While revolutionary at the time, Upledger himself emphasized that much of his theory was provisional and would evolve with future research.10 The model offered a useful way to conceptualize the CSR for teaching purposes, and Upledger encouraged openness to new ideas and scientific testing.

Building on this foundation, Rasmussen introduced the Pacemaker Theory, offering a contemporary neurophysiological explanation of the CSR. The theory is supported by decades of multidisciplinary evidence, bringing CST closer to the language of neuroscience and physiology, while honoring Upledger’s pioneering contributions. The theory provides a mechanism that aligns with Upledger’s clinical observations, while situating CST within a broader body of neurophysiological research.

The Pacemaker Theory positions the CSR as one of several neurogenic rhythms—autonomously generated patterns of electrical activity produced by networks of oscillating neurons located in the brain stem near the fourth ventricle.11 These neurons act as central pacemakers, producing rhythmic discharges independent of respiration or cardiac rhythms. The autonomic nervous system integrates multiple physiological systems and serves as a critical conduit for communication between a central pacemaker in the brain stem and peripheral oscillators in vascular structures.

Peripheral oscillators in smooth muscle and endothelial tissues contribute to vasomotion—the rhythmic contraction and relaxation of blood vessels.12 When vasomotion is regulated by neural impulses rather than local metabolic factors, it is called neurogenic vasomotion. This centrally driven vasomotion is believed to be modulated by a brain stem pacemaker that communicates descending regulatory signals primarily via sympathetic spinal tracts.

The central autonomic network—a coordinated system of cortical, subcortical, and brain stem structures—acts as the integrative hub linking the pacemaker with wider physiological systems to maintain homeostasis.13 Within this framework, the CSR is understood as a system-wide oscillatory rhythm generated at approximately 6 cpm.14 It is transmitted throughout the body via neurogenic vasomotion, resulting in oscillations in blood vessel diameter, tissue pressure, and fluid flow. These oscillations are not confined to any specific region; rather, they can be palpated throughout the body by skilled practitioners. Ultimately, the Pacemaker Theory provides a scientifically plausible, biologically grounded framework for understanding the CSR as a legitimate neurophysiological rhythm.

The Body’s Built-In Life-Sustaining Rhythms

The body depends on foundational physiological rhythms—such as breathing, heartbeat, digestion, and circadian cycles—all regulated by neural oscillators. These specialized networks of neurons, or central pattern generators (CPGs), generate rhythmic electrical activity that persists even in the absence of external stimuli.15 Each rhythm has a steady baseline but remains flexible and responsive to physiological demands. For example, respiratory rate adjusts during stress or exertion but returns to baseline afterward. This capacity for modulation, governed by systems like the pre-Bötzinger complex and sinoatrial node, maintains homeostasis.16 When disrupted, these rhythms can lead to systemic dysfunction.17 These principles inform how CST practitioners perceive and work with the CSR as a fundamental organizing rhythm.

Physiological Rhythms Generated by Oscillating Neurons

Oscillating neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems create self-sustaining rhythmic patterns through intrinsic properties and synaptic architecture. These neural oscillators generate rhythms critical for survival, underpinning vital autonomic and cognitive functions such as locomotion, sleep, and breathing. Recent models show that rhythmic behaviors emerge not from a single neuron but from networks of oscillators synchronizing over time—what researchers call network synchrony. They arise from interactions involving excitatory and inhibitory circuits, ion channels, and gap junctions.18 Tools such as EEG, MEG, and local field potentials enable detection and study of these rhythms. Though difficult to isolate to single neurons, modern neuroscience identifies regions where rhythm generation occurs and tracks how they influence bodily systems.19 Dysfunction in synchronization can lead to disorders such as arrhythmia, Parkinson’s disease, or sleep disorders. Computational neuroscience continues to explore how these rhythms arise, interact, and relate to body systems, offering insight into how rhythms—like the CSR—can potentially affect global physiology.20

Empowering Manual Therapists

For today’s manual therapist, the growing body of research on the CSR is working to validate what has been palpated for decades, deepening our understanding of why this work matters. By understanding the CSR through the lens of the Pacemaker Theory—as a neurogenic vasomotor rhythm rooted in brain-stem pacemakers and expressed throughout the body—practitioners can appreciate how their light, respectful touch interfaces with core physiological processes.

This scientific clarity empowers therapists to integrate CST into their practice with greater confidence, knowing that when they work with around 5 grams of pressure, as Upledger emphasized, they are using a gentle manual approach that resonates with the body’s rhythms to support balance, resilience, and healing.

Notes

1. Thomas R. Rasmussen and Karl C. Meulengracht, “Direct Measurement of the Rhythmic Motions of the Human Head Identifies a Third Rhythm,” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 26 (April 2021): 24–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.08.018.

2. William G. Sutherland, The Cranial Bowl (Free Press Company, 1939).

3. Dr. John E. Upledger coined the term "CranioSacral Therapy," and this spelling and capitalization are unique to his work.

4. Rasmussen and Meulengracht, “Direct Measurement of the Rhythmic Motions of the Human Head Identifies a Third Rhythm.”

5. Rasmussen and Meulengracht, “Direct Measurement of the Rhythmic Motions of the Human Head Identifies a Third Rhythm.”

6. Nicette Sergueef et al., “The Palpated Cranial Rhythmic Impulse (CRI): Its Normative Rate and Examiner Experience,” International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine 14, no. 1 (March 2011): 10–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijosm.2010.11.006.

7. Sergueef et al., “The Palpated Cranial Rhythmic Impulse (CRI): Its Normative Rate and Examiner Experience.”

8. Rasmussen and Meulengracht, “Direct Measurement of the Rhythmic Motions of the Human Head Identifies a Third Rhythm;” K. E. Nelson, N. Sergueef, and T. Glonek, “Laser-Doppler Flowmetry and Cranial Rhythmic Impulse,” Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 101, no. 9 (2001): 457–66; Kenneth E. Nelson, Nicette Sergueef, and Thomas Glonek, “Recording the Rate of the Cranial Rhythmic Impulse,” Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 106, no. 6 (June 2006): 337–41, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16790539.

9. Nelson, Sergueef, and Glonek, “Laser-Doppler Flowmetry and Cranial Rhythmic Impulse;” Nelson, Sergueef, and Glonek, “Recording the Rate of the Cranial Rhythmic Impulse.”

10. John E. Upledger and J. D. Vredevoogd, CranioSacral Therapy (Eastland Press, 1983).

11. Sergueef, Nelson, and Glonek, “The Palpated Cranial Rhythmic Impulse (CRI): Its Normative Rate and Examiner Experience.”

12. Nelson, Sergueef, and Glonek, “Laser-Doppler Flowmetry and Cranial Rhythmic Impulse;” Eduardo E. Benarroch, “The Central Autonomic Network: Functional Organization, Dysfunction, and Perspective,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 68, no. 10 (October 1993): 988–1001, doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(12)62272-1; Claude Julien, “The Enigma of Mayer Waves: Facts and Models,” Cardiovascular Research 70, no. 1 (April 2006): 12–21, doi.org/10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.008.

13. Jack L. Feldman and Christopher A. Del Negro, “Looking for Inspiration: New Perspectives on Respiratory Rhythm,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7 (March 2006): 232–42, doi.org/10.1038/nrn1871; Benarroch, “The Central Autonomic Network: Functional Organization, Dysfunction, and Perspective.”

14. Sergueef, Nelson, and Glonek, “The Palpated Cranial Rhythmic Impulse (CRI): Its Normative Rate and Examiner Experience.”

15. Eve Marder and Dirk Bucher, “Central Pattern Generators and the Control of Rhythmic Movements,” Current Biology 11, no. 23 (November 2001): R986–96, doi.org/10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00581-4.

16. Marder and Bucher, “Central Pattern Generators and the Control of Rhythmic Movements;” Feldman and Del Negro, “Looking for Inspiration: New Perspectives on Respiratory Rhythm;” O. Monfredi and M. R. Boyett, “Sick Sinus Syndrome and Atrial Fibrillation in Older Persons—Role of Sinoatrial Node, Atrial Fibrosis, and Aging,” Heart Rhythm 12, no. 4 (2015): 1089–97, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25668431.

17. O. Monfredi and M. R. Boyett, “Sick Sinus Syndrome and Atrial Fibrillation in Older Persons—A View from the Sinoatrial Node Myocyte,” Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 83 (June 2015): 88–100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.02.003; L. Glass, “Synchronization and Rhythmic Processes in Physiology,” Nature 410 (2001): 277–84, https://doi.org/10.1038/35065745.

18. Monfredi and Boyett, “Sick Sinus Syndrome and Atrial Fibrillation in Older Persons—Role of Sinoatrial Node, Atrial Fibrosis, and Aging.”

19. Marder and Bucher, “Central Pattern Generators and the Control of Rhythmic Movements;” György Buzsáki and Andreas Draguhn, “Neuronal Oscillations in Cortical Networks,” Science 304, no. 5679 (June 2004): 1926–9, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1099745.

20. Buzsáki and Draguhn, “Neuronal Oscillations in Cortical Networks.”