Handling Head Trauma

Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Massage Therapy for the Common and Serious Injury

Imagine a head injury that changes your life. Maybe you got hit in a hockey game or were in a car wreck, or maybe you got into a fight and took a blow to the head. Or maybe you just stumbled and hit your head on a table. In that moment, everything changes. After a long recovery period, you are still struggling. Your ability to express yourself—gone. Your motor control—iffy at best. Your reflexes—slow and unreliable. Maybe you have seizures, headaches, insomnia, and you can feel your mental capacities slipping away. In another era, your doctor might have called you “punch-drunk.” Once upon a time, your friends might have called you a “slugnut,” and stories about your accident would recall that time you “got your bell rung.”

And how popular is this topic today? In a nonscientific poll, when I asked for input from massage therapists about their experiences with head injuries, so many people responded that an internal support group was proposed, specifically for massage practitioners who have this history.

Here, we'll look at the spectrum of head injuries, from the not-so-mild “dings” to the severe and even fatal complications related to repeated injuries and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). And we will discuss the role of bodywork for people who have had experiences like this.

Vocabulary Review

Before we dive in, some basic vocabulary review will make this information more accessible.

-

Contusion—This is a specific area of swollen tissue in the brain. Contusions tend to happen in predictable locations.

-

Coup-contrecoup—This is an injury in which the brain hits one side of the cranium, and then the other side. This can lead to contusions, diffuse axonal injury, bleeding, inflammation, and cerebral edema.

-

Diffuse axonal injury—This involves a twisting or shearing movement of the brain within the cranium, leading to swollen and disconnected axons. It happens in a lot of head injuries but often doesn’t show on imaging tests.

-

Open-head injury, closed-head injury—Open-head injuries involve full-thickness skull fractures and a risk of life-threatening infection, along with brain damage. By contrast, closed-head injuries carry little risk of infection, but they also involve secondary damage due to inflammation and cerebral edema.

-

Second impact syndrome—This is a situation in which a person with a still-swollen brain injury sustains another injury, as when an athlete returns to play too soon and sustains another head injury. Because of the way cerebral inflammation and edema work, second impact syndrome can cause enough pressure inside the cranium that the brain bulges or even herniates across the falx cerebri or into the foramen magnum. This kind of injury can result in disability or death.

We think of our brains as well protected from external injuries, and for the most part they are. But when an external collision is hard enough, things can go downhill fast. Head injuries occur across a range of severity, from mild to fatal. They often cause only short-term damage, but they may also lead to unpredictable longer-term problems, one of which may become progressive and dangerous.

Head injuries are not rare. About 3 million ER visits per year are related to traumatic brain injury (TBI), with about 250,000 hospital admissions, including about 70,000 deaths. We often associate head injuries with healthy young people playing contact sports, but the population most at risk are older adults who may have unsteady gaits or dizzy spells. Taking blood thinners, which is especially common in this population, makes serious complications more likely.

What Happens with a Head Injury?

When a person has an external collision that is severe enough to affect the brain, two types of tissues are most likely to be affected: neurons and their supplying blood vessels. Damage to either or both tissues elicits an inflammatory response, which makes things worse.

Neuronal Damage

Under normal circumstances, neurons produce a variety of proteins called tau. Tau proteins support and hold neurons in correct spatial relationships: Think of them as the scaffolding that supports the neurons in the brain. A head injury can cause the neurons inside the cranium to stretch or spiral, or the whole brain can knock from one side of the cranium to the other in a coup-contrecoup event. Neuronal damage, which can occur from external injury, sustained inflammation, or other causes, alters how tau proteins are produced and how they work. The tau molecules bend, fold, twist and accumulate in places where they don’t belong.

If the person [who has had a head injury] feels safe when they come for a massage, they are likely to have a positive outcome.

Ultimately, instead of supporting neuronal function, they interfere with it. In some cases, these changes become self-perpetuating, and the damage progresses even without further external injury or inflammation. This also describes one of the components of Alzheimer’s disease and might explain why dementia is often a part of long-term head injury consequences.

Damaged Blood Vessels and Inflammation

Bleeding (hemorrhaging) and trapped blood (hematoma) can occur within the working cells of the cerebrum, on the surface of the brain, or both. In any case, neurons in the area are damaged or killed off, and inflammation—or even death—is the result. Brain inflammation can disrupt neuronal spatial relationships and function. Inflammation can compromise the blood-brain barrier, so dangerous chemicals can access the central nervous system. Ultimately, it can lead to permanent neurodegeneration.

In addition to the consequences of torn blood vessels, post-injury edema may restrict cerebral blood flow. A cascade of chemical reactions follows, ultimately killing off functioning neurons.

Various Head Injuries

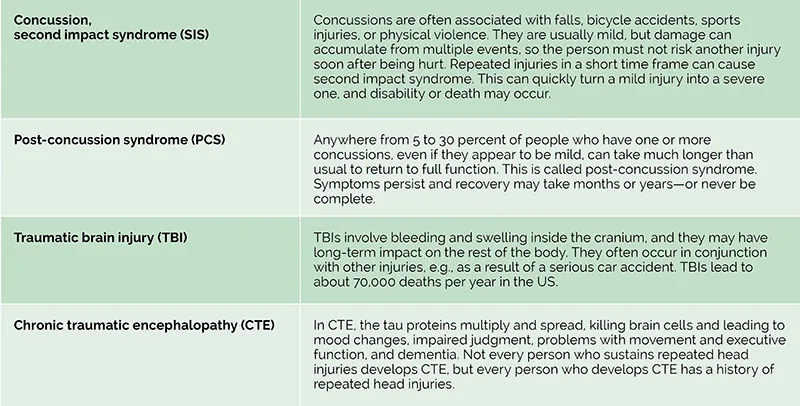

Head injuries are highly variable, and some carry higher risks of complications than others. Because head injuries are so common, many clients are likely to have had one or more of these in their history, and it may be helpful to understand the different types (see “Types and Consequences of Head Injuries”).

Signs and Symptoms, Complications

The signs and symptoms seen with concussions and TBIs obviously depend on the circumstances, the severity of the injury, and the parts of the brain that might have been affected.

In the short term, signs of a brain injury include loss of consciousness, a change in mental status, disorientation, loss of balance, amnesia, seizures, and other signs. But if other injuries have occurred, like if the person was in a car wreck, the brain injuries might not be immediately obvious. Sometimes the effects of a TBI don’t show for several hours or days.

The most common symptoms patients report in the days and weeks after a brain injury include fatigue, weakness, cognitive difficulties, memory problems, headache (including severe migraines), tremors, loss of coordination, dizziness, and anxiety. If these persist more than six months, the person might be diagnosed with post-concussion syndrome.

Many patients develop aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after their event, and posttraumatic depression, along with suicidal ideation, is also common. TBI survivors also have a higher-than-average risk for heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.

Serious TBIs that involve disability and lengthy rehabilitation also carry higher-than-typical risk for deep vein thrombosis, spasticity, and heterotopic ossification—calcium deposits that develop in soft tissues. All of these have implications for bodywork, especially in an inpatient setting, so it’s important to be aware of these possible complications.

A TBI complication that has gotten a lot of public attention is CTE—this is ongoing, progressive brain damage resulting from multiple head injuries over a long period of time. We usually associate this with American football players, but it dates back to at least 1928, when Dr. Harrison Martland documented a condition that he called “punch-drunk syndrome” within a group of professional boxers. In 2005, Dr. Bennet Omalu published his findings regarding former Kansas City Chiefs player Mike Webster, who died of a heart attack at age 51. Since then, many other events related to American football, soccer, hockey, rugby, and other sports have been attributed to CTE. In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke published public statements about the link between repetitive head injuries and CTE risk.

TBI survivors have a higher-than-average risk for heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.

At this point, CTE can only be definitively identified posthumously. A brain bank has been established at Boston University so people who suspect they have CTE can donate their brains for study. This may allow us to develop better tools to identify and treat CTE.

Treatment Options

Treatment options for people with TBI are limited to dealing with the aftermath of the brain damage. Patients may be recommended to pursue physical therapy, occupational therapy, talk therapy, and speech and language therapy to help them develop or relearn skills and cope with new limitations. Massage therapy can also be part of this picture, if it is done with compassion, patience, and sensitivity.

That said, brain injury survivors can pose some specific challenges for massage therapists to address. Here are some key points that were shared with me from some individuals working in this field:

-

“The [client] interview is part of the therapy. It can take them a long time to spool out their story, and they [can] get bounced around health-care providers who can’t give them the time they need. It probably won’t come out in order, but in disjunctive elements—trust that there will be a feeling that the story has been told. And that’s when the autonomic state begins to shift.”—M. H. (MT)

-

“Long-lasting vertigo means turning over on the table or coming to a seated position may be risky for them if they are unattended. This is something that would be good to know in advance obviously.”—C. H. (MT and TBI survivor)

-

“Many [clients] struggle with executive function and remembering details, so it’s good to use a schedule of reminders leading up to the day of their appointment.”—C. H. (MT and TBI survivor)

-

“We can help people remember that they are making progress, even when they can’t see it themselves.”—L. C. (MT and TBI survivor)

Everything we know about head injuries, challenged nervous systems, and clients who have been through trauma points in one therapeutic direction: If the person feels safe when they come for a massage, they are likely to have a positive outcome. Not positive as in, “Wow, my head injury is healed and it’s like it never happened!” But positive as in, “I am so relieved to have this space to feel calm and not overstimulated.”

That sense of safety may be a little different for each client, and it may require some advance preparation and imagination to offer a client the best treatment for their needs. With a good team of providers, strong support, and persistence, people with a history of head trauma can, if not fully recover stronger than before—like a broken bone—find ways to cope, manage their symptoms, and live a full and satisfying life that is not severely limited by a head injury.

A Deeper Dive—Multiple Bike Accidents

Michael Hamm is a massage therapist and CE provider who specializes in neurological issues. Here, he describes one of his clients with a long and complicated TBI history.

“My client came to me about 10 years after a couple of serious accidents where she’d been knocked off her bike by a car. Early in her recovery, she had a hard time and went through a couple of suicide attempts. But when I saw her, she was active—volunteering for her church, riding her bike, and doing things outdoors.

“She still struggled with sensory experiences that reminded her of her accidents, like ambulances or flashing lights. These could trigger a PTSD response: barely functioning on the outside, while her nervous system was going haywire inside. Because she had to drive through heavy traffic to see me, she would often be pretty spun up when she arrived. What she really needed was to feel safe, and then she could learn some ways to regulate her nervous system and her pain.

Eventually, she recognized that initial trauma response and took action to try to control it with breathing and thinking about other things. And now it doesn’t leave her exhausted for hours.”

A Deeper Dive—A Car Crash That Changed Everything

In 2011, Chasity Nelson was T-boned in a motor vehicle accident. She had a severe closed-head traumatic brain injury (TBI), 22 broken bones, and a collapsed lung and spleen damage. She spent a month in a medically induced coma, followed by time in TBI rehabilitation.

“My short-term memory was gone,” Nelson says. “You could ask me a question, and two minutes later I’d have no idea what you asked. I couldn’t draw a clock. I had to relearn how to walk, everything.”

By 2014, she was much recovered and decided she wanted to provide care for others as she had received, so she enrolled in massage school. She has been practicing for eight years and specializes in working with people who have temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders and head, neck, and shoulder pain.

Contributors

I want to extend my deep gratitude to the individuals who generously helped me write this piece, as well as to the bodywork professionals who shared their thoughts, observations, and findings to bring their best skills to head injury survivors. You can read their stories in “Multiple Bike Accidents” (page 59) and “A Car Crash That Changed Everything” (page 62) or see my interview with Lauren Christman, a massage therapist and head injury survivor who specializes in working with this population, in the accompanying video.

-

Lauren Christman, LMT, CCST, BCSI/ATSI: craftedtouch.com/teachers/laurens-extended-bio; craftedtouch.com/craniosacral-therapy/certification-program

-

Michael Hamm, LMT, CCST: integrativebodyworkeducation.com; mikehammseminars@gmail.com

-

Chasity Nelson, MT: massagebook.com/therapists/chasity-nelson-massage-and-bodywork-

Resources

Ainsworth, C. R. Medscape. “Head Trauma.” Last modified May 22, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/433855.

Brown, L. “CTE Risk More Than Doubles After Just Three Years of Playing Football.” The Brink. October 7, 2019. https://bu.edu/articles/2019/cte-football.

Burns, S. L. “Concussion Treatment Using Massage Techniques: A Case Study.” International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork 8, no. 2 (June 2015): 12–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26082825.

Burton, K. W. Medscape. “CTE Common Among Young Athletes in Largest Brain Donor Study.” August 28, 2023. https://medscape.com/viewarticle/995923.

Chaphalkar, A. Medscape. “Early Biomarkers in the Detection of Traumatic Brain Injury.” October 15, 2024. https://medscape.com/viewarticle/early-biomarkers-detection-traumatic-brain-injury-2024a1000is2.

Concussion Alliance. “Massage Therapy.” Accessed August 25, 2025. https://concussionalliance.org/massage-therapy.

Ginsburg, J., and T. Smith. Traumatic Brain Injury. StatPearls Publishing, 2025. http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557861.

Grashow, R. et al. “Perceived Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and Suicidality in Former Professional Football Players.” JAMA Neurology 81, no. 11 (September 2024): 1130–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.3083.

Hossain, I. et al. “Tau as a Fluid Biomarker of Concussion and Neurodegeneration.” Concussion 7, no. 2 (December 2022): CNC98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36687115.

Legome, E. L. Medscape. “Postconcussion Syndrome.” Last modified September 24, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/828904-overview.

May, T., L. A. Foris, and C. J. Donnally III. Second Impact Syndrome. StatPearls Publishing, 2025. http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448119.

Verrill, D. S. Medscape. “Classification and Complications of Traumatic Brain Injury.” Last modified March 19, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/326643-overview.

Yasgur, B. S. Medscape. “Traumatic Brain Injury and CVD: What’s the Link?” January 18, 2024. https://medscape.com/viewarticle/traumatic-brain-injury-and-cvd-whats-link-2024a10001g6.