Erik Dalton said that the buttocks have probably been assigned more syndromes than any other region of the human body. This is no surprise as the biomechanical forces in this area are complex, and two major nerves—the sciatic and the pudendal—weave their way through a crowded landscape of muscles, ligaments, and tendons. Add the tremendous torsional stress transferred through the pelvis and lumbar spine during walking, sitting, and lifting, and you have a recipe for pain syndromes that are notoriously difficult to pin down.

In this article, we’ll define deep gluteal syndrome (DGS), discuss the biomechanical and behavioral factors that contribute to dysfunction, and outline a holistic treatment plan that aims to “level the tail.”

What Is Deep Gluteal Syndrome?

DGS is an umbrella term for several conditions where the sciatic nerve or other peripheral nerves passing through the gluteal region become compressed or irritated by muscles, connective tissues, or vascular structures (Image 1).

By focusing on the common root dysfunction of weak glutes and overworked deep rotators, therapists can cut through the confusion [of syndromes and symptoms].

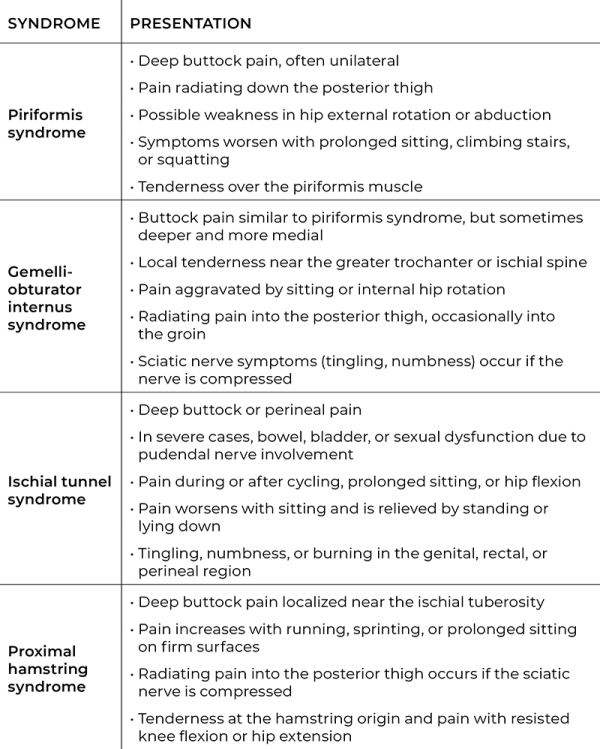

Unlike lumbar radiculopathy (where nerve irritation originates in the spine), DGS involves entrapment at the level of the hip and pelvis, most often beneath or between the muscles of the deep six lateral rotators. While sciatic nerve entrapments are the most common, the definition extends to entrapments of the pudendal, superior and inferior gluteal nerves, obturator, and posterior femoral cutaneous nerves. Massage therapists are most familiar with the following syndromes:

-

Gemelli-obturator internus syndrome involves compression of the sciatic nerve by the tendon of the obturator internus and the adjacent superior and inferior gemelli muscles as the nerve exits the pelvis.

-

Ischial tunnel syndrome refers to entrapment of the pudendal nerve as it travels near the ischial spine or between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments. Compression of the pudendal nerve can cause pain, tingling, or numbness in the perineum.

-

Piriformis syndrome occurs when the piriformis muscle compresses the sciatic nerve as it passes beneath or through the muscle in the greater sciatic notch. This entrapment is the most well-known presentation of deep gluteal syndrome.

-

Proximal hamstring syndrome involves compression of the sciatic nerve against the ischial tuberosity by hypertrophy, fibrosis, or scarring of the proximal hamstring tendons. It is a primary suspect when symptoms arise in athletes with chronic hamstring overload or injury.

Other syndromes that fall under the DGS umbrella are superior and inferior gluteal nerve entrapments, obturator nerve entrapment, posterior femoral cutaneous nerve entrapment, and quadratus femoris syndrome.

Each of these syndromes has distinct anatomical features but causes overlapping symptoms (see “Under the Deep Gluteal Syndrome Umbrella”). This overlap makes accurate assessment difficult without the use of imaging or extensive orthopedic testing.

Biomechanical and Behavioral Contributors

Nerves in the gluteal region travel through some narrow spaces. Even subtle alterations in posture, muscle tone, or tissue integrity can lead to nerve entrapment. Several factors contribute to dysfunction in this region:

-

Biomechanical factors: Weak or inhibited gluteal muscles disrupt the balance between the large gluteal muscles and smaller stabilizing muscles. When the glutes fail to generate sufficient extension, abduction, or external rotation, the deep rotators are forced into compensatory roles beyond their stabilizing function.

-

Gait mechanics: Faulty patterns such as excessive foot pronation, contralateral pelvic drop, or reduced hip extension alter load transfer across the pelvis and hip. These compensations increase strain on the hamstring origin, piriformis, and obturator internus, predisposing them to overuse and fibrosis.

-

Lifestyle: Prolonged sitting, whether occupational or recreational, weakens gluteal activation and shortens the hip flexors. In sedentary individuals, this reinforces the same dysfunction observed in more athletic or traumatic presentations.

-

Postural habits: Lumbar hyperlordosis, anterior pelvic tilt, and prolonged standing position can cause the pelvis to tilt in a way that increases tension on the deep rotators and shortens the hip flexors. These adaptations diminish gluteal recruitment and promote overactivation of the deep six.

-

Repetitive activities: Running, sprinting, cycling, and heavy lifting place high demands on hip extension and stabilization. If the glutei are not adequately recruited, the deep rotators and proximal hamstrings absorb repetitive loads, raising the risk of entrapment syndromes.

-

Trauma: Falls onto the buttocks, hamstring strains, or pelvic fractures may result in fibrosis, adhesions, or hematoma formation that narrow the gluteal space and tether nearby nerves.

Across these influences, the clinical pattern remains consistent: gluteal inhibition with compensatory overuse of the deep rotator muscles.

A Common Root Dysfunction

This imbalance between the gluteal muscles and the deep rotators represents the root dysfunction underlying many entrapment syndromes of the hip. The deep six lateral rotators (Image 2) are piriformis, superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, obturator internus, obturator externus, and quadratus femoris. Originating from the sacrum and ischium and inserting on or near the greater trochanter, they provide fine-tuned stabilization of the femoral head within the acetabulum and assist with lateral rotation during weight-bearing activities.

Surrounding these stabilizers are the larger gluteal muscles. Gluteus maximus generates powerful hip extension and external rotation, while gluteus medius and minimus control abduction and frontal-plane stability, especially during single-leg stance. Ideally, the glutei handle the bulk of postural and locomotor demands, allowing the deep six to remain focused on joint centration and stabilization.

When gluteal function is inhibited, however, the body recruits the deep six as prime movers. Over time, this compensation produces hypertrophy, repetitive microtrauma, and increased resting tone within the confined boundaries of the deep gluteal space. Even minor changes in muscle bulk or tension can compress adjacent neurovascular structures such as the sciatic or pudendal nerves. Erik Dalton often turned to these two techniques to reduce tension in the deep six and stimulate underactive gluteus muscles.

Releasing the Deep Six External Hip Rotators

This technique aims to reduce tone in the deep six to help restore functional alignment and reduce strain on the pelvis. Apply this technique to both sides of the body and reduce your pressure if the client reports discomfort (Image 3).

With the client prone, stand on their left side, facing their head. Flex the client’s left knee and hook your left arm around their ankle. Rest your right forearm lateral to the sacrum, where you can feel the fibers of the external rotators. Drop the client’s foot toward the floor to place a stretch on the external rotators. Ask the client to press their ankle against the left side of your body to contract the external rotators for a count of five, then relax. Drop the client’s foot toward the floor until you encounter the next restrictive barrier. Repeat this technique three times.

Spindle Stim for the Glutei

Spindle stimulation is a targeted technique used in Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques to “wake up” inhibited muscles. The goal is to stimulate and reset the muscle spindle reflex by rapidly compressing the muscle belly in a specific direction. This technique sends a strong excitatory signal to the central nervous system, helping the brain re-engage the gluteal muscles (Image 4).

Place the client’s left leg in a figure-four position, which tightens parts of the gluteal fibers. While standing on the client’s left side, apply soft fists in a fast-paced oscillating maneuver over the left-side gluteal muscles, working across (not with) the muscle fibers for two minutes. Don’t lift your fists as with tapotement. Keep constant pressure on the muscle fibers.

Options: You can also extend the client’s leg so it hangs off the therapy table on the side you are activating, or you can ask the client to engage in slow pelvic tilts or slow inhalations and exhalations. At the same time, apply spindle stim against the muscle’s “grain.” These movements engage different gluteal fibers, enhancing the technique and producing broader effects.

Beyond the Deep Six and GluteI

Beyond releasing the deep rotators and reactivating the gluteal muscles, Dalton promoted “leveling the tail” to improve biomechanical function, reduce protective muscle spasms, and prevent or treat symptoms holistically. While there isn’t room for a comprehensive protocol here, you’ll also want to think about:

-

Gait mechanics and pelvic alignment: Address faulty gait and pelvic asymmetry by releasing overactive hip flexors such as the iliopsoas and rectus femoris, stretching shortened adductors, and strengthening the gluteus medius, minimus, and maximus to restore pelvic stability and hip extension.

-

Hamstrings: Reduce excessive load at the ischial tuberosity by releasing restrictions at the proximal hamstring tendons, lengthening hamstring bellies when shortened, and reinforcing balanced hip-extension mechanics through coordinated hamstring and gluteal strengthening.

-

Pelvic ligaments hip capsule: Support pudendal nerve health by releasing tension in the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments and mobilizing the posterior hip capsule to preserve joint centration and maintain space for neurovascular structures.

-

SI joints: Improve load transfer across the pelvis by mobilizing the sacroiliac joints, releasing erector spinae and quadratus lumborum guarding, and strengthening stabilizers like multifidi and transverse abdominis to support sacral leveling.

In Closing

We’ve learned that the buttocks is a complicated region, with the sciatic nerve and other peripheral nerves weaving through layers of muscles, ligaments, and tendons under constant torsional stress. That complexity explains why so many syndromes have been named here and why symptoms are often difficult to untangle.

By focusing on the common root dysfunction of weak glutes and overworked deep rotators, therapists can cut through the confusion. Instead of chasing labels, the goal is to restore balance, “level the tail,” and help clients move with greater stability and less pain.

Resources

Benson, E. R., and S. F. Schutzer. “Posttraumatic Piriformis Syndrome: Diagnosis and Results of Operative Treatment.” The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 81, no. 7 (July 1999): 941. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199907000-00006.

Boyajian-O’Neill, L. A. et al. “Diagnosis and Management of Piriformis Syndrome: An Osteopathic Approach.” Journal of Osteopathic Medicine 108, no. 11 (November 2008). https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2008.108.11.657.

Dalton, E. Erik Dalton Blog. “Deep Gluteal Syndrome and Tendinopathy: Getting to the Bottom of Buttock Pain . . .” Accessed August 30, 2025. https://blog.erikdalton.com/deep-gluteal-syndrome-and-tendinopathy.

Dalton, E. Erik Dalton Blog. “Low Back Piriformis SI Joint Pain.” Accessed August 30, 2025. https://blog.erikdalton.com/low-back-piriformis-si-joint-pain.

Hopayian, K. et al. “The Clinical Features of the Piriformis Syndrome: A Systematic Review.” European Spine Journal 19 (2010): 2095–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1504-9.

Martin, H. D. , M. Reddy, and J. Gómez-Hoyos. “Deep Gluteal Syndrome.” Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery 2, no. 2 (July 2015): 99-107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27011826.

Papadopoulos, E. C., and S. N. Khan. “Piriformis Syndrome and Low Back Pain: A New Classification and Review of the Literature.” Orthopedic Clinics of North America 35, no. 1 (January 2004): 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00105-6.

Robert, R. et al. “Anatomic Basis of Chronic Perineal Pain: Role of the Pudendal Nerve.” Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 20 (March 1998): 93–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01628908.

Stafford, M. A., P. Peng, and D. A. Hill. “Sciatica: A Review of History, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and the Role of Epidural Steroid Injection in Management.” British Journal of Anaesthesia 99, no. 4 (October 2007): 461–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aem238.