Thirty trillion cells make up the human body, but the body is not only made of cells. These cellular superstars are woven together by a living scaffolding called the extracellular matrix—a fabric of protein fibers and watery gels that provides structural support and gives the human body its recognizable form.

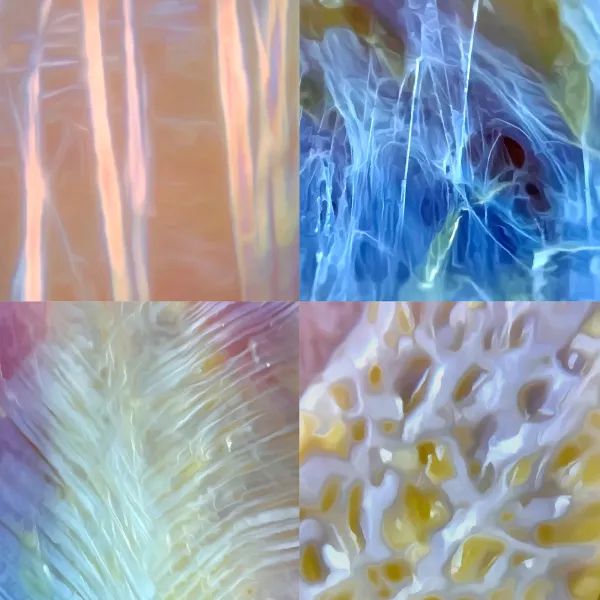

Within every corner of this matrix lives a remarkable cell: mechanosensitive, shape-shifting, and endlessly industrious. Every time we reach overhead for a book, carry groceries up the stairs, or lean across a massage table, this cell reads the tension in our tissues and responds by weaving, unraveling, and reweaving the fabric that holds us together (Image 1). Yes, the web has a weaver—meet the fibroblast.

Understanding fibroblasts changes how we think about the tissue we touch. It gives us insight into a cellular conversation happening beneath our hands, explaining why lasting change takes time and how our therapeutic touch informs that change.

Making the Matrix

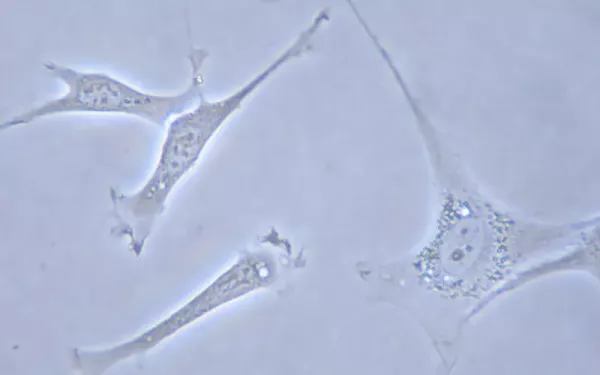

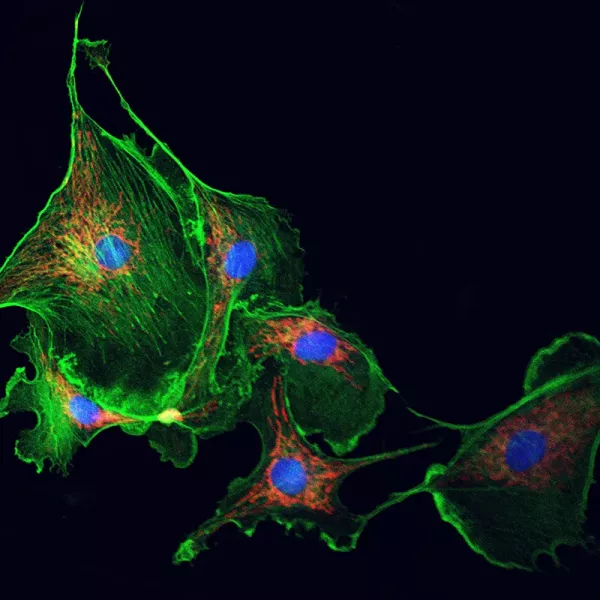

Billions of fibroblasts exist throughout the human body. Under a microscope, the fibroblast often appears spindle-shaped, but its shape isn’t static. When called to action, the fibroblast can shape-shift, sending out starfish-like projections of its cell membrane to leverage as arms that help it crawl along and through the extracellular matrix, contorting itself between fibers to get to where it’s going (Image 2). As its name suggests, the fibroblast’s specialty is making fibers. Like textile fabrics, the fabric of the human body is made of fibers. But instead of cotton or wool, the body’s fabric is woven from the protein fibers of collagen and elastin.

Collagen dominates the anatomical landscape, accounting for 30 percent of all proteins in the human body and acting as the glue that holds together those 30 trillion cells. The collagen matrix spans from the skin at the body’s surface, through our subcutaneous fat and fascia, surrounding every muscle fiber, and continuing deep to the bone. The matrix’s fibers envelop every cell and form the scaffolding of every organ, from head to toe. Our heart’s muscle fibers exist in a heart-shaped matrix of collagen, and our liver cells live in a liver-shaped matrix of collagen. And so it is with all the organs. Even our bones are a collagen matrix that has been mineralized. Collagen is everywhere. And fiber by fiber, the fibroblasts weave the collagen to create the framework of the entire human form.1

The matrix’s fibers envelop every cell and form the scaffolding of every organ, from head to toe.

While the quantity of collagen produced is important, the orientation and density of the fibers may be even more important because they determine the mechanical properties of each tissue. Just as textile fibers can be woven into different patterns—from a loose jersey knit to the tight basket weave of canvas—collagen fibers can be arranged to serve completely different functions. Fibroblasts tightly arrange collagen fibers in parallel to create tendons, the iliotibial (IT) band, and the plantar fascia to allow for force transmission. But in other tissues, like the skin’s dermis, fibroblasts interweave fibers in multiple directions and layers, creating a tough yet flexible tissue that can stretch and return to its original shape. This precise organization reflects the specific mechanical needs of each tissue (Image 1).

Sensing Tension in the Matrix

The collagen matrix is quite dynamic, with the capacity to actively remodel itself to meet the changing biomechanical needs of growth, performance, healing, and repair. How do the fibroblasts know what to change and remodel? We send them signals with everything we do. Fibroblasts constantly monitor the matrix and respond as needed based on mechanical input.

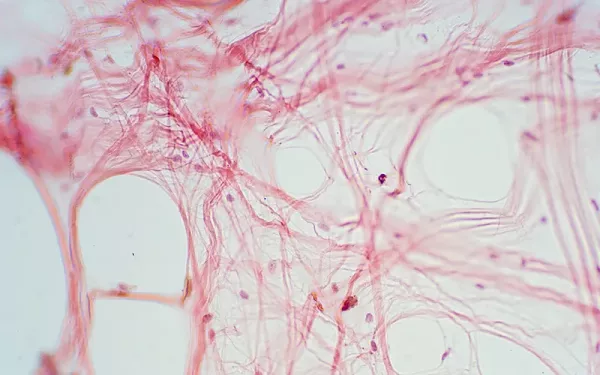

The body’s tissues are under constant mechanical load from the demands of gravity, walking, jumping, stretching—even the squeeze of a petrissage stroke in a massage session. Whether small or large, each of these loads creates distortions in the collagen matrix, and the fibroblasts feel it because they are mechanosensitive (Image 3). They have an exquisitely fine-tuned ability to perceive and respond to mechanical signals in the matrix.

As mechanical forces stretch and deform the matrix, the fibroblast cells are deformed, allowing the fibroblasts to convert mechanical inputs into chemical signals through a process called mechanotransduction. This is how loading creates change. The matrix is loaded, causing a distortion. The fibroblasts feel the pull, which gets converted into chemical signals. The signals then elicit a physiological response that enables the fibroblasts to get to work—producing more collagen, breaking down existing fibers, or releasing cytokines to coordinate with the immune system.

Whether you have heard of mechanotransduction, you are probably already familiar with the concept. In the same way bones strengthen in response to weight-bearing exercise and muscles grow larger when challenged with resistance training, fibroblasts respond to mechanical forces by adapting the collagen matrix.

Custom Building the Matrix

Mechanically stressing the collagen matrix causes the fibroblasts to respond with a new design. Like with any remodeling job, it doesn’t happen overnight. Little by little, the structure and organization change. Over time, the fibroblasts write the history of individual movement patterns and postural habits into the tissues, custom-building and reinforcing the collagen matrix based on the mechanical information provided. A good example of this is how the IT band develops. Humans aren’t born with an IT band; fibroblasts weave this fascial reinforcement into the collagen matrix. As young children transition from crawling to walking upright on two legs, the mechanical loads on the matrix change. In response, the fibroblasts create the needed thickened reinforcement along the lateral thigh: the IT band. The same holds true for each person’s unique postural habits. Carry a bag every day on your left shoulder? Always stand with your weight shifted over your right leg? The fibroblasts pay attention and reinforce the matrix with collagen fibers to accommodate these repeated and regular loads.

Remodeling works both ways. Periods of minimal loading also send information to the fibroblasts. If you’ve ever worn a cast after an injury, you might have experienced less range of motion once it was removed. Curious about this phenomenon, researchers put casts on the hind legs of rats for 12 weeks. The expected result at the macrolevel was reduced range of motion, which was the case. But what changed at the microlevel in the tissues was unexpected. By the end of week 12, the fiber orientation in the matrix of the immobilized leg became more irregular. Without mechanical loading, fibroblasts lacked the input to organize new fibers properly. The result was a random pattern that created more stiffness.2 The big takeaway here: When it comes to your mechanically sensitive fibroblasts, input is everything.

When there’s an injury in the matrix, fibroblasts shift from their routine maintenance work into repair mode. Whether the injury is from a surgical incision or a scratch from a cranky cat, fibroblasts respond by weaving more collagen threads into the matrix. The result? Scar tissue. During tissue repair, fibroblasts do more than spin out new collagen; they help coordinate the healing response. They monitor both mechanical forces and inflammatory signals simultaneously, allowing them to adapt their repair work to changing conditions in real time. Some fibroblasts transform into myofibroblasts, specialized cells with contractile properties that can physically pull wound edges together while continuing to produce new matrix material.

Touching the Matrix

In addition to neurological responses, fluid dynamics, and other mechanisms of the human form, understanding how fibroblasts change tissue at the cellular level provides insight into how our hands create change in clients’ tissues. We’re not just massaging muscles or “breaking up adhesions.” We’re providing mechanical information to a living, adaptable, three-dimensional matrix that responds to our input. The next time you work with a client, remember, you’re not just touching tissue, you’re having a direct conversation with the fibroblasts.

That dialogue will continue to influence the matrix long after a session ends. In every stroke, every stretch, every moment of sustained pressure, you’re speaking the language that fibroblasts understand—the language of mechanical force. And they’re listening and responding by reweaving the very fabric of the human form.

Notes

1. The body’s collagen network is maintained by the fibroblasts and a related family of mesenchymal-derived cells, including tenocytes (tendons/ligaments); chondroblasts/chondrocytes (cartilage); osteoblasts/osteocytes (bone); and keratocytes (cornea).

2. Minoru Okita et al., “Effects of Reduced Joint Mobility on Sarcomere Length, Collagen Fibril Arrangement in the Endomysium, and Hyaluronan in Rat Soleus Muscle,” Journal of Muscle Research & Cell Motility 25 (April 2004): 159–66. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jure.0000035851.12800.39.